At Cranford High School, Learning the Language of the Caesars via Modern-Day Technology

At Cranford High School, students are gaining new fluency in the language of Virgil, Cicero, and Horace by using software that’s designed to bring it alive for them.

A grant from the Cranford Fund for Educational Excellence paid for the software by eyeVocab, which combines thought-provoking pictures with written and spoken words to make Latin vocabulary stick in one’s memory.

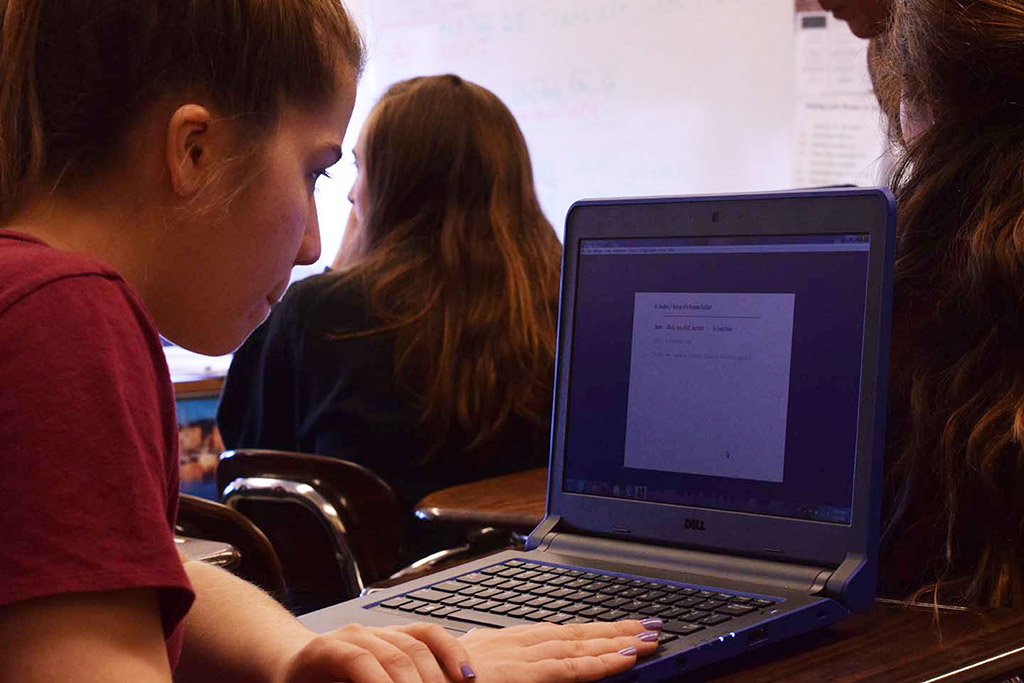

It’s proving effective, and students find it absorbing. “It just seems like they’re in their element when using it,” said Annamaria Bellino, supervisor of world languages, English language services, and family and consumer sciences for the Cranford schools.

Many students take Latin to build their English vocabulary in preparation for college entrance exams, said Latin teacher Aileen McGuire, who along with Mrs. Bellino applied for the grant. But students don’t hear or see Latin used the way they do English, of course, which is one reason the software piqued Mrs.McGuire’s interest.

The software debuted in January, helping students from Latin II through advanced placement prepare for their midterms. Mrs. McGuire has already seen an uptick in some students’ quiz scores, along with new enthusiasm and engagement in Latin classes, in part because of the chance to work independently.

“It really does allow for differentiation (among students) much more easily,” Mrs. McGuire said.

Unlike vocabulary drills led by the teacher from the front of the classroom, in which each students’ mistakes may be heard by all, the program gives students more privacy, as well as control over their pace. Listening to the program via headphones, they quiz themselves over and over until they get all the words right, giving the teacher more latitude to give one-on-one help or present more challenging lessons.

“I think partly because no one really is seeing their progress and their performance through the software, because it is somewhat private when they’ve got the earphones on, it’s more motivating,” Mrs. McGuire said.

Each word is introduced with a picture—often offbeat or humorous—that only hints at its meaning; “apple” might be signified by a picture of an apple tree, for instance. After studying the image, students see the Latin word on screen, hear it spoken, and see the corresponding English word and syntax information as well.

This complex “scaffolding of information” builds suspense and helps students retain the words better than if they were given simpler definitions, Mrs. Bellino said.

Because of the software’s possibilities for building vocabulary skills, Mrs. McGuire has set more ambitious translation goals for the students than she would have if they were using their textbooks alone.

“It definitely has changed my whole perspective toward teaching, because I can really develop these skills at even higher levels earlier because of the technology,” she said.